An extension to Hofstadter's modes of thinking

In Douglas Hofstadter’s classic Godel, Escher and Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid 1, “MU” refers to both the puzzle he uses to introduce the idea of formal systems, as well as the two modes of thinking humans use with such systems: M-Mode is the mechanical mode, I-Mode is the intelligent mode.

Before I introduce two more modes – D-Mode, or Deep Mode and S-Mode or Shallow Mode – let’s look at the puzzle and how it relates to thinking about problems:

The MU puzzle

“MIU” is a made-up formal system with just a 3-character alphabet (M, I and U) and four rules (given below). The goal is to start with the string “MI”, apply the rules in any combination and arrive at “MU”.

The rules:

- You can append “U” to the end of any string (e.g.

MI --> MIU) - You can double the substring following the M (e.g.

MIU --> MIUIU) - You can replace 3 consecutive I’s with a U (e.g.

MIIII --> MUI) - You can get rid of 2 consecutive U’s (e.g.

MIUUI --> MII)

You can apply these rules in any order, any number of times to try and arrive at “MU”.

Try it. You won’t find a solution. If you go about this mechanically, like a program would, you would go on forever. But unlike programs, human beings are intelligent enough to think about the system outside the rules, or in Hofstadter’s words, to jump out of the system. These, then are the two modes.

M-Mode is when you think within the system, using only its rules and axioms. I-Mode is when you think about the system from the outside. Only in I-Mode will someone notice that these rules can’t give you “MU” (Hofstadter also hints at a Zen-like “U” mode, which I won’t go into here).

I have met many people over the years who do their jobs almost entirely in M-Mode: given a set of rules (and responsibilities), they will execute their jobs mechanistically, never bothering (and sometimes actively avoiding) going into I-Mode: thinking about problems outside the given rules. After years of habitual M-Mode thinking, activating I-Mode seems too much of a burden.

D-Mode and S-Mode

Sometimes M-Mode can be useful when you have to do tedious tasks that are the mental equivalent of locating a needle in a haystack. For me, this is usually wading through 1000 lines of application logs and tracing the execution path through code to look for a failure, or, while researching a topic, tracking down all significant references to it in books and articles.

But M-Mode is not going to work if you’re not thorough. Suppose the MU puzzle had a solution. If you’re going to look for it mechanically, you can’t randomly apply rules here and there, abandoning strings and starting over haphazardly when a solution isn’t forthcoming. You have to systematically cover every possibility, applying every rule to the starting string, and then applying every rule to each resulting string and so on (this constructs a tree).

But for those whose aversion to I-Mode is due to laziness, this type of thinking is even worse than I-Mode – it’s not just difficult, it’s boring. So what most of them really operate in is what I’d call MS-Mode, or Mechanical Shallow mode. You only follow the rules given, but you don’t explore the full implications of even those rules.

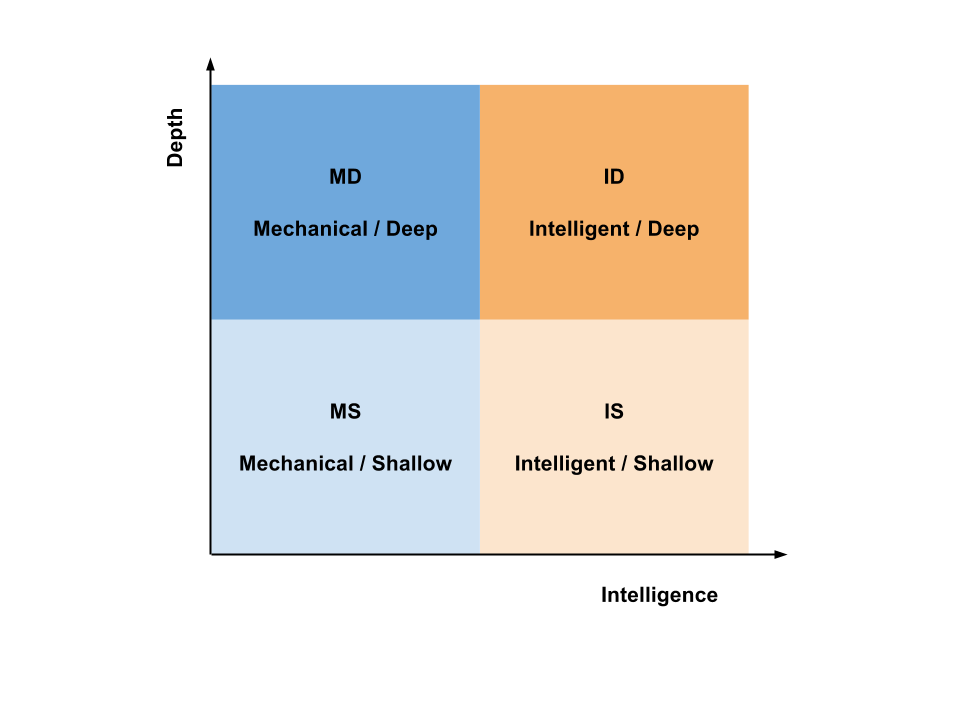

By inference, I think you can now figure out the remaining modes:

Most human beings operate in the MS quadrant most of the time, especially at leisure. There are lots of traditional jobs that require you to go into MD quadrant: proofreading, accounting, law, etc. Science and engineering tends to operate on the top two quadrants (MD and ID). Philosophy (with the exception of the likes of Bertrand Russell) and psychology, in my opinion, tend to operate in the IS quadrant. The ID quadrant is mostly inhabited by mathematicians.

As you must have already guessed, the ID quadrant is the place to go if you want to solve difficult problems. It is also the most mentally taxing. Another day, I will talk about how this relates to software engineering.

-

I’m halfway through the book as I write this. ↩